THE ILLUSIONS OF FREE-TO-PLAY

February 2021From freemium products to open-source projects to marketplaces to UGC platforms, free-to-play games are already everywhere.

On December 8th, 2020, Adobe announced the end of Flash. And soon after Zynga announced the end of Farmville. This type of “end-of-an-era” moment evoked not only nostalgia but a heightened awareness of sunk cost — the sweat and soul we’ve poured into a world that once felt as real and omnipresent as nature itself.

Like many others who grew up in a metropolitan city, where the growing number of test prep books was inversely correlated with the few open slots at top-tier schools, I resorted to multiplayer games as a way to socialize with friends during long summer nights. Early on in my teenage years, I’ve internalized that under the veil of “free-to-play”, everything came at a cost. Being in a fictional world doesn’t mean that we’re far removed from economic reality. The games we play — from MMORPG, MOBA, NeoPets, MySpace — despite being completely free-to-play, the cost of winning was something only a few could afford. For an average player, we can either pay cash in exchange for an improved or a faster grind, or we maximize our odds by investing our attention and time to infinity. Even though the public school system in China attempts to eliminate the idea of the socioeconomic class by enforcing strict uniform protocol, even heavily regulating the style of one’s backpack, we could still discern the nuances by how one allocates their leisure time. The opportunity cost is high for those whose family’s economic future relies on the performance of their college entrance exam. The cost is just as high for those whose physical freedom had been pledged to the metagame that their parents signed up for on their behalf the moment the kids were born. Despite the “free” public education system, parents can always pay a fee in addition to a generous gift to the admission officers to secure a spot at an “important school”. Whenever there’s a free-to-play game, a path of paying-to-win emerges, and the price isn’t always money.

Unless you’re Farmville.

The game’s perpetual cash trap is a brutalist manifestation of the notorious “pay-to-win” model. Just a decade ago, 19% of Facebook’s revenue came from either advertising or payments tied to Zynga games — fertilizers that get your crops to grow faster, the ante to play another round of poker, the McDonald’s sign that shows up in your town. But we keep playing because what was once complementary to the lack of “third place” in the physical world is now filled with social serendipity and imagination. It’s our duty to help our friends farm grow. It’s our duty to take care of the land we build. After pouring $3000 into Clash of Clans just to stay on the Top Players’ Rank, Jorge Yao got featured by the New York Times.

They painted a picture of an escapist:

Here was a guy who had been the captain of the high school rugby club and served as treasurer of his college fraternity, lost in a new city and trapped in a 300-square-foot studio. Clash had the round-the-clock promise of camaraderie. It made Mr. Yao feel less isolated. The members of North 44 — an elite clan that one can join only by invitation — became a family to him. He will tell you even now that he loves them like brothers.

If Clash of Clans was a legitimate sport, Yao may have been a masterful coach:

When a member of North 44 would quit the game, Mr. Yao would take over his account. Then Mr. Yao would use one of his multiple accounts to attack himself when he needed a shield. In order to pull this off, though, he had to keep all of these other accounts highly ranked, which meant playing as many as five accounts at the same time, around the clock.

Yet this is what Yao said in the interview: “Looking back, I think I must have been insane.” To be insane is to be disassociated and removed from reality, and to deny the world of Clash of Clans as a legitimate entity. Indeed, in the end, Yao may have been left with nothing but a bunch of iPads, but what if what he built was real all along? Real tribe. Real relationships. Real challenges.

For the past year, I found myself venturing deeper into the psychology, economics, and culture of “free-to-play”, a set of sophisticated mechanics and vernacular that not only led to a Cambrian explosion of the gaming industry but has already permeated every corner of the Internet. From freemium products to open-source projects to marketplaces to UGC platforms, free-to-play games are already everywhere. It feels as if we’ve lived through an era that Chris Andersen once described in his 2009 book “Free: The Future of a Radical Price”:

This new form of Free is based on the economics of bits, not atoms. It is a unique quality of the digital age that once something becomes software, it inevitably becomes free—in cost, certainly, and often in price. (Imagine if the price of steel had dropped so close to zero that King Gillette could give away both razor and blade, and make his money on something else entirely—shaving cream?) And it’s creating a multibillion-dollar economy —the first in history—where the primary price is zero.

...

The twentieth century was primarily an atoms economy. The twenty- first century will be equally a bits economy. Anything free in the atoms economy must be paid for by something else, which is why so much traditional free feels like bait and switch—it’s you paying, one way or another. But free in the bits economy can be really free, with money often taken out of the equation altogether. People are rightly suspicious of Free in the atoms economy, and rightly trusting of Free in the bits economy. Intuitively, they understand the difference between the two economies, and why Free works so well online.

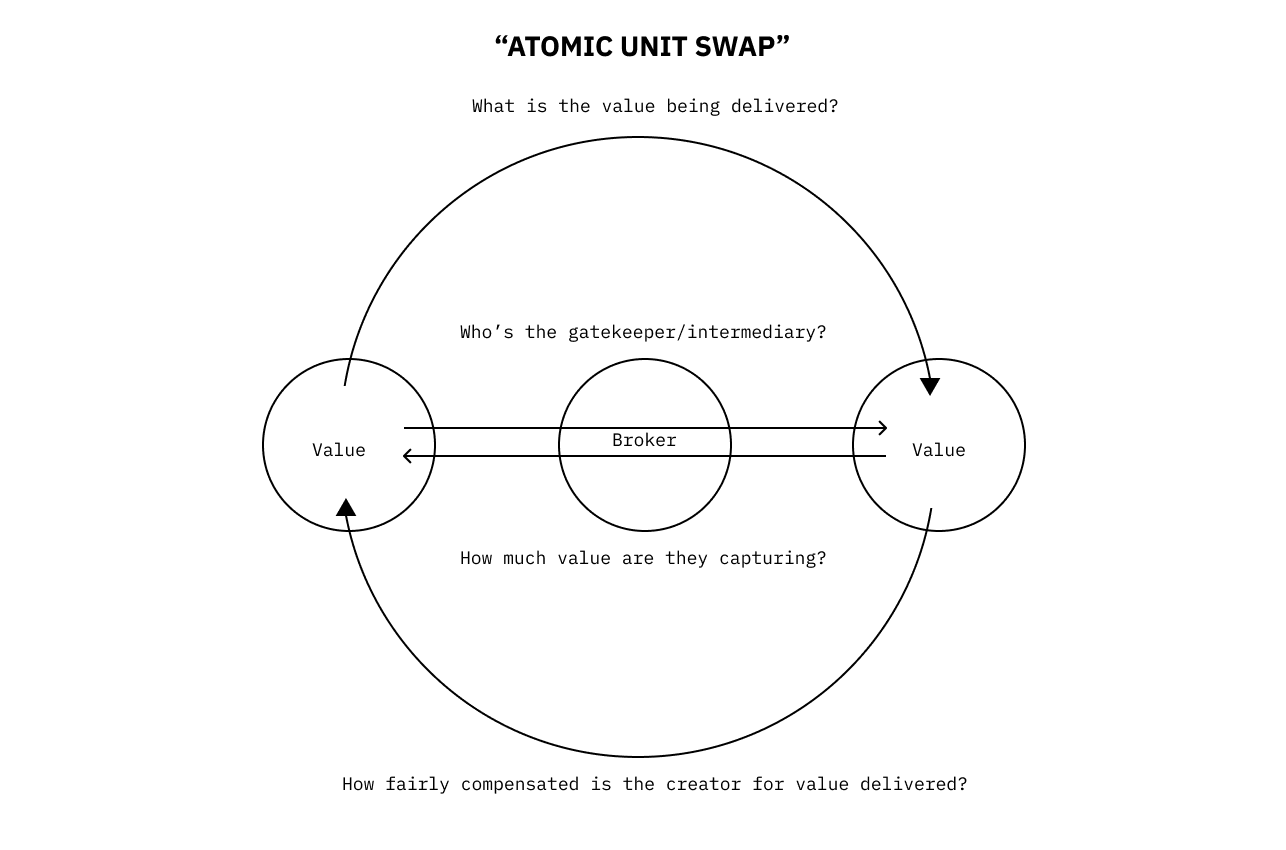

Fast forward a decade later, the boundless supply of information and the rapidly decreasing cost of storage and compute seem to have indeed turned traditional economics upside down. What was once unimaginable, like accessing all the best university courses around the world, has become as accessible as grabbing a copy of free newspapers at a corner street diner. Though we all know the saying: "there’s no free lunch in the world,” the convenience of tech platforms has blunted our senses to our economic reality. The addictive feedback loop, mesmerizing marketing campaigns, and the accelerated cadence of the hype cycle make it more difficult than ever to discern both the true price and the true cost of something. At Pace, our discussions are frequently anchored around the concept of “Atomic Value Swap”, which is defined eloquently by Chris in his frameworks:

An Atomic Value Swap is the measurement of the sustainability of repeated core transactions in an ecosystem. Payment for goods or services is an example of an atomic value swap, one where cash is exchanged for an item or service. Both parties deem the transaction to be beneficial and therefore the transaction occurs. If the price of a product or service is too high, the buyer will not engage in the transaction.

The “free-to-play” game design has been berated as sneaky and manipulative, luring the players to trade “something” for “nothing”. Such assumption implies that real-world currency definitionally warrants more economic value than the virtual one. We all know that this is no longer true. Not only has the game economy grew to become a hundred billion dollar industry, but the perceptions of what we perceive as valuable have also largely evolved. The hours that Yao has invested in, the kinship, camaraderie, and memories that he has created for North 44 could’ve been valued by both social and financial rewards, distributed fairly among the members based on contribution.

Prior economic analysis of the gaming industry, due to its virtual nature, has considered games to be a substitute for other leisure activities like golfing or traveling. Every hour we spend on games is an hour subtracted from working hours that earn us wages, and every penny we spend on games is a penny we could’ve spent on other leisure activities and a penny subtracted from our income.

In traditional utility maximization problems, time and money appear as constraints, the relief of either always results in higher utility. Yet there appears a new set of constraints introduced by gaming, where the relief of constraints may actually reduce emotional satisfaction, and hence result in lower utility. In other words, the challenges in games inspire creativity and therefore overall utility, a counterintuitive stance in an increasingly frictionless world.

If the utility can be higher when a constraint is tougher, then there can be a willingness to pay for tougher constraints. Talking to a few open source developers who contribute to the latest packages or a few DeFi experimenters who bear the skyrocketing gas cost may be a good way to test this hypothesis.

Another major shift happens when there are tangible social or monetary rewards from playing games. In traditional economics, we have price as a cost of goods, and wage as the price of leisure, but the new possibility arrives when the income from playing exceeds income from what traditionally would be considered “labor”. Or even a more radical thought would be that the time spent on games are substitutes for work time, and work time just another type of game. In order to maximize the utility function above, an agent in a perfectly “free-to-play” world would naturally be drawn to the games that create the most emotional satisfaction, which is a result of acquiring social or financial rewards or overcoming constraints and challenges. The motivation to participate in a game can be manifold, but generally, participants are no longer simply consumers who exchange their labor wage with leisure time, rather they’re looking for challenges and constraints in the hopes of social recognition and self-actualization.

The allure of the “free” has been a marketing technique since the dawn of capitalism. Now it’s manifesting as a 14-day free trial. A free drink with three tacos. A no-fee brokerage account. A free credit report. Our brains mostly interpret "free" in monetary terms. We’re sophisticated enough to know that free-to-play mechanics are oftentimes marketing techniques for customer acquisition, but we’re not yet sophisticated enough to intuitively grasp the atomic value swap on Internet platforms — the price we pay to participate in seemingly “free-to-play” games.

We feel good about installing Honey and reading The Points Guy because we subconsciously interpret the exchange as an arbitrage we exploit in the system by being “smart”, while hours pass by as we conduct our due diligence. All of our behaviors are then closely studied by algorithms and data analysts, so more offers to get sent to our doorsteps with companies that know more about ourselves than even our close-friends do, with promises that felt too-good-to-be-true.

The illusion of “free-to-play” is at its core the illusion of costlessness. As participants in these newfound “free-to-play” games, we are as powerful as we’re powerless. For every action we take, we are either being sold as products or we are facilitating the sale of the product, most of the time without being fairly compensated for it.

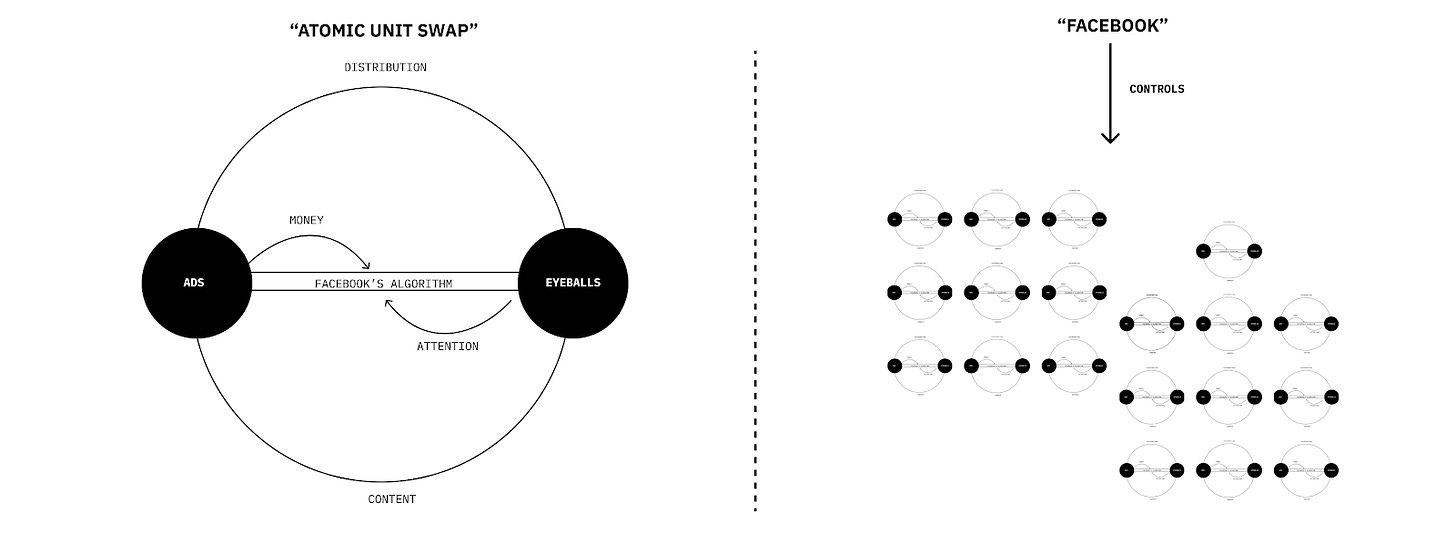

Google has invented an effective engine to convert from reputation (PageRank) to attention (traffic) to money (ads). Social media companies like Facebook/Twitter have invented an engine to convert from user-generated content (creative asset) to attention (algorithm & traffic) to money (ads). Google and Facebook play the roles of central bankers for our attention economy. They represented a generation of “free-to-play” games that unlocked infinite consumer surplus and participation, and with increasing power as the brokers of the value exchange, they now require “paying to win”.

The price we pay with our attention, time, reputation, and even health have been broadly understood by recent analyses. Yet what remains under-discussed, and I’d argue will become much more pivotal in the next decade of the consumer internet is the cost of our very own identities. People have poured hearts and souls to become who they are on these “free-to-play” platforms. It’s hard to delineate if they’ve become who they are because of these platforms, or it’s because of who they are, these platforms become vibrant. The aggregated effect of identity creation at scale is not linear but geometric, accounting for not only for quantity and price of products being created and exchanged, but also another dimensionality of mutual emotional investment that compounds with every interaction.

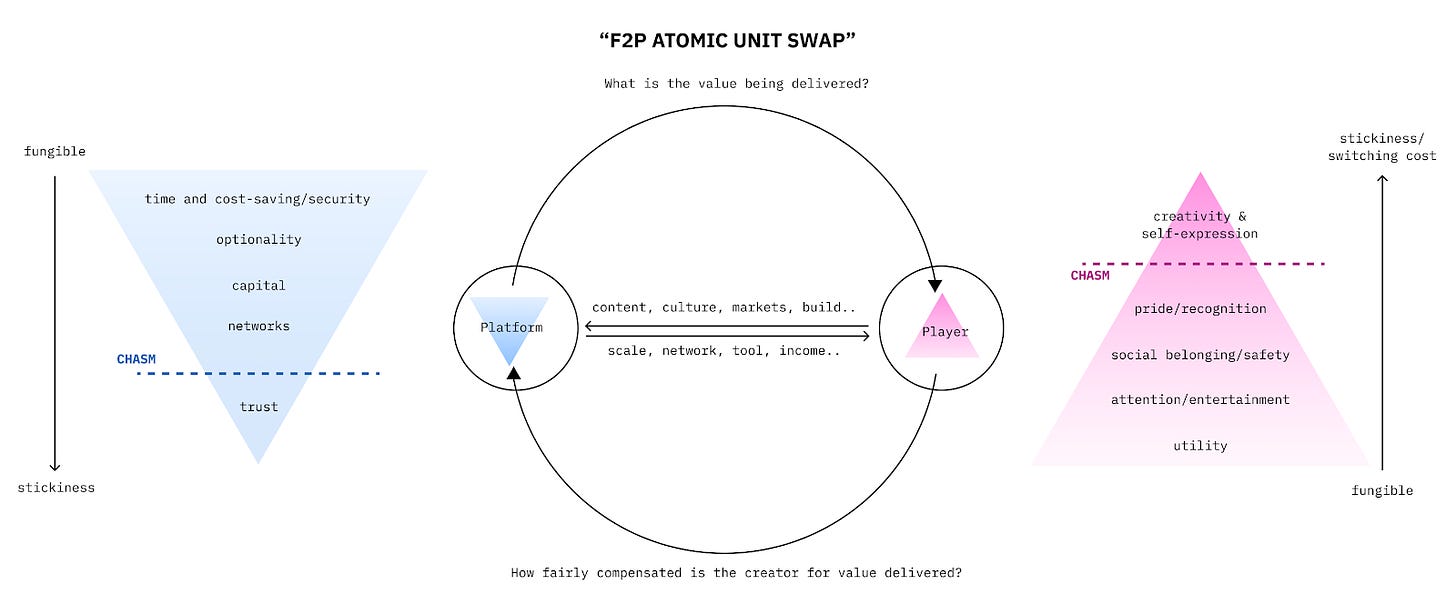

The becoming of TikTok creators, Figma designers, Shopify owners, Substack writers, Robinhood traders, credit card gurus, and late-night ASMR Clubhouse hosts also entail a collective movement of “becoming” and “unbecoming”. As participants, they deeply understand that platforms would be capturing their labor as value, so they’re incentivized to go to whatever platforms that let them do their best work and have the most fun. Regardless this manifests in the form of “come for the tool, stay for the platform”, or “come for the network, stay for the tool”. They are different iterations of the same intrinsic desires.

With the iconic Fortnite at the helm, a new type of “free-to-play” games understood deeply the coming-of-age moment for the evolving psyche of the internet-native generation, who decidedly pick the game not because they can cheat, but because there are infinite ways they can win. Players no longer “pay to win”, rather the games are “free to win”. Instead, they “pay to belong” or “pay to find themselves”. To be the most skilled at the game is only one dimension of winning. A player can also win by flexing the coolest cosmetics, gaining access to once-in-a-game-time events, and participating and gaining social status in a metagame that emerges outside of Fortnite itself (e.g. becoming a streamer with a big following). With its scale of 350 million players globally and $5B in revenue, Fortnite gives us a glimpse into the vision of a digitally-native “Metaverse”. In an interview, the CEO of Epic Games Tim Sweeney articulates the definition:

Metaverse is it’s not just built by one mega corporation [...] It’s gonna be the work, the creative work of millions of people who can each add their own elements to it through content creation and programming and design. And the other way of adding value.

So it will be a massively participatory medium of a type that we really haven’t seen yet. And even though you have Fortnite and Minecraft and Roblox each manifest some aspects of it, I think we’re still pretty far from having the thing. But yet the talk about this thing is it’s not just the work of one company. It’s not just one company’s product or revenue stream. We’re talking about a mass participatory media, which needs to be an economy if there’s not an economy underlying this thing.

The Metaverse idea isn’t new. It’s simply another metaphor that represents an ecosystem, a metaphor that has been propagated by urban designers and business school professors for the past decades. “The DNA of the company”, “the ecology of the marketplace”, “the pulse of a city” and so on are all attempts to understand the unpredictable fluctuations of man-made entities through the lens of nature, who’s familiar with the cycle of birth, maturity, and death.

Not all cities and not all companies actually evolve into a self-sustaining ecosystem that allows people to prosper, regardless how meticulously the creators may have designed them. While urban planners, economists, and policy makers primarily focus on a city’s physicality rather than on the people who inhabit them, cities are much more than just the physicality of the buildings and structures. Similarly, for a long time until the last wave of Internet companies, company builders and analysts primarily focused on a company’s assets, liabilities and operational structures rather than the people interacting via the product.

Shakespeare long understood our fundamental symbiotic relationship with cities. In one of the dramas Coriolanus, a Roman tribune named Sicinius rhetorically remarks, “What is the city but the people?” to which the people respond, “True, the people are the city.”

In his book “Scale”, British physicist and the former president of Santa Fe Institute Geoffrey West gave a definition of the city as a phenomenon:

[Cities are] complex adaptive social network systems resulting from the continuous interactions among their inhabitants, enhanced and facilitated by the feedback mechanisms provided by urban life.

The concept of Metaverse might be an ultimate manifestation of a “free-to-play” driven digital economy, and it’s the first time a complex, adaptive ecosystem such as a city can theoretically be rendered in the virtual world in lossless fidelity. Even companies like Google and Facebook, whose value is driven by the advanced sorting and indexing of digital information, still have to rely heavily on the demand generated from the physical world.

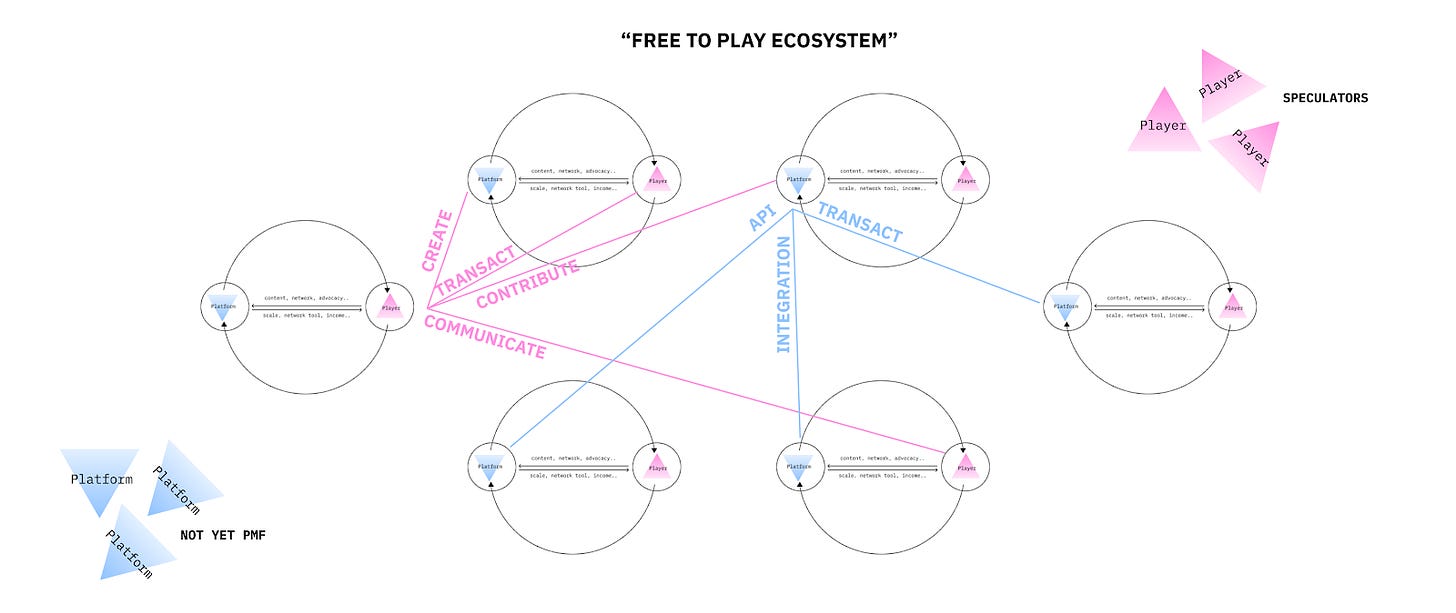

The foundation of a successful city is the sustainable value exchange between people — employment, wealth, religion, creation, innovation, the spread of diseases, healthcare, crime, education, entertainment, and so on. Without these activities, we can hardly call a city successful, the same way we can hardly call an Internet-native platform successful without these interactions. Through that lens, the vision of the Metaverse is still in its nascency and requires meaningful work to be done. The overarching concept around complex and adaptive social networks that make cities prosper helps us delineate the shape of an ecosystem that’s filled with potential energy awaiting conversion into kinetic energy. Fortnite is one example of a platform with potential to become a larger ecosystem, so are Discord, Reddit, Figma, Shopify that provide scale, tools, income, and network in exchange for content, markets, culture, and innovation. These emerging dynamics are illustrated below through the lens of Atomic Unit Swap:

Rather than an overly general statement such as “if you’re not paying for it, you’re the product,” this piece aims to clarify the illusions of costlessness by distilling the value exchanges on digitally native platforms by peeling the layers of platform and player psychology. Despite the marginal cost of software production trending to zero as Andersen predicted, the virtual ecosystem still shares the similar properties with cities as a socioeconomic organism. The cost of participating in the new “free-to-play” platforms not only denominated in time and money as traditionally economics understood, but also in emotional satisfaction provided by challenges, social recognition, and self-actualization. The deeper a platform can penetrate the player’s identity needs, the stickier the platform becomes and the higher the switching cost. For an individual player who’s now inundated with “free entries” to platforms, the fewer platforms that offer the most nonfungible value wins. Not all players on a given platform forge their identities on the platform, but the few who do will tend to drive most of the value. Similarly, not all platforms would need to foster ongoing trust on top of networks and capital, but the few who do will accrue the most value.

Existing analyses on Internet ecosystems that focus solely on their existing asset efficiency without analyzing the social, economic, and emotional needs of the players would be missing the much bigger picture. Just like city dwellers, players in virtual ecosystems can nimbly travel between different pockets of the ecosystem and pick a few to find their people, while the digital infrastructure, unlike the physical one, has its unique ability to communicate and update one another to be continuously adaptive and evolutionary through pipes built between them.

German scholar Schivelbusch believed that the development of railways and communication systems generated a socio-spatial transformation of the urban environment. The new infrastructure gave passage to the flux of people, goods, and information across the traditional sociospatial orders, erased the traditional forms and figures of the city. This “annihilation of space” in the 19th century produced the need and the desire for new forms or figures of the urban environment. There were attempts to retain forms and figures, all were lost with the emergence of the modern cities.

If every new world entails the annihilation of another, then what do the new forms and figures look like to supplement the semantic emptiness of our current environment that’s augmented by the four walls that we lawfully stay behind, for the betterment of our collective future? All meanwhile, the “free-to-play” games are up and running, on a global scale, inviting us to participate and continue to infuse the emptiness with newfound meanings.