MEANING-FINDING ON THE INTERNET

May 2020

The current crisis will give birth to a new narrative revolution.

In the original Greek, apocalypse doesn’t mean the catastrophe; it means the uncovering.

My friend who shared this slice of profundity was boasting the water-color painting he just finished. He said he hasn’t picked up a paintbrush since high school, and in his own words, “painting has been more fun than Netflix.”

This crisis is uncovering what I didn’t know I was capable of — like cooking, dancing, and sitting at my desk for 12 hours straight to poke around a Javascript library.

It’s also uncovering the frailty of the physical world and the imperfection of our current social fabric — the lies we tell ourselves that are that much more justifiable when commutes were busier, meetings were longer, and OKRs were clearer.

My proficiency with shortcuts, productivity tools, and swiss grids is attained at a cost of suppressing and backlogging our messy, unprocessed emotions. The feelings, which remain unclaimed and uninterrupted, manifest themselves as directionless anxiety. We feel a compulsive need to remain busy, clinging to a jam-packed schedule that ensures we don’t have to confront the scary thoughts. I fear small talks because I’m terrible at them. Especially when the other person on the line asks:

“Okay. I get it that your work is going great. How are you though? Like, how are you feeling?”

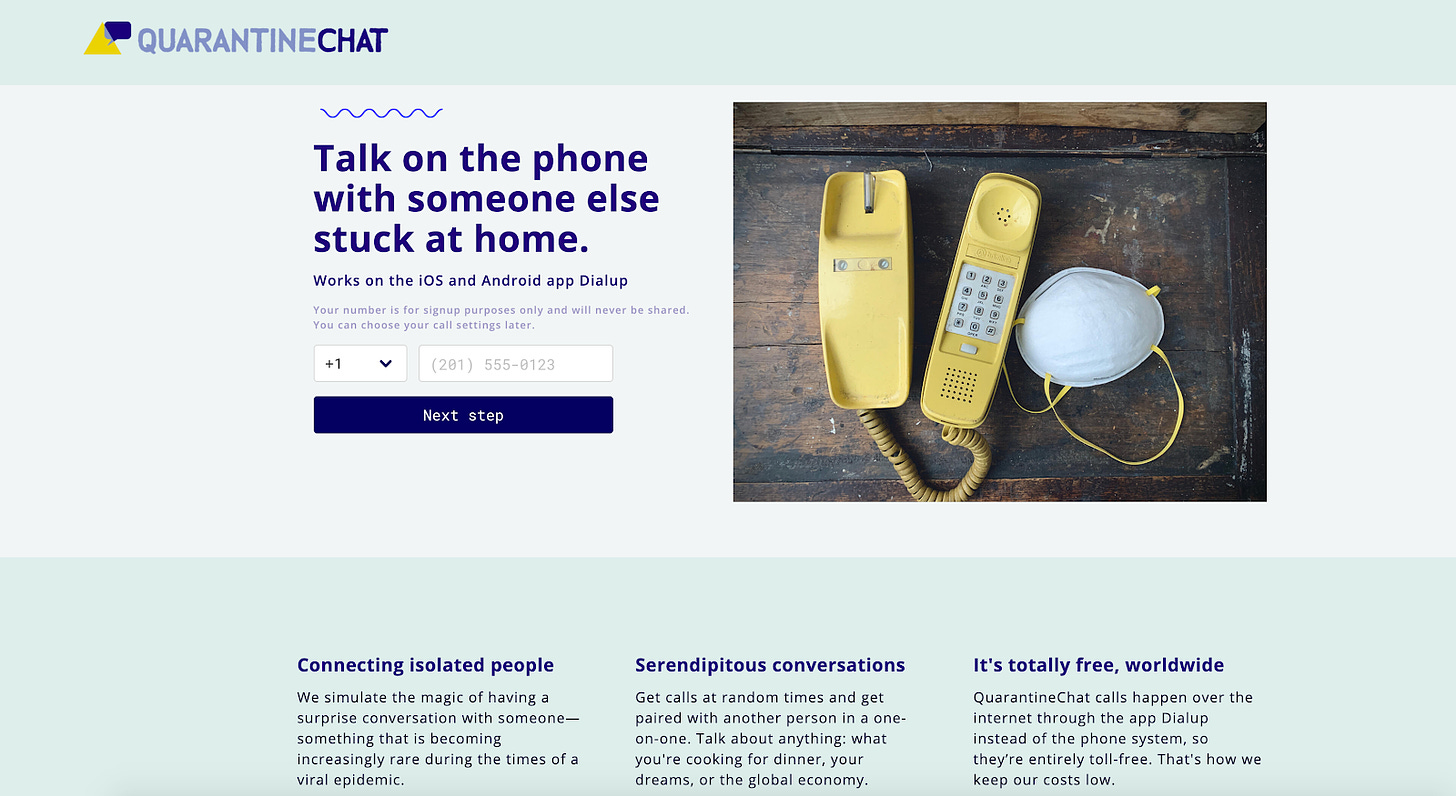

A tool built by the lovely team behind Dialup

A tool built by the lovely team behind DialupWhen we were shuffling in the busy streets of NYC, distractions are readily accessible — the Apple gold coating of my quip toothbrush, the windows XP dark blue of my Away suitcase, and the vaporwave pastel of my Glossier eyeshadow are all extensions of my technophilic fantasy.

Anna Wiener writes in her Silicon Valley memoir Uncanny Valley: “when tech products were projected into the physical world they became aesthetics unto themselves as if to insist on their own reality.” For a while, I found comfort in this reality. The aspirational rhetoric of these brands has helped me name my own needs that I did not know I have. I’ve found it much easier to have a conversation intellectualizing the optimal best practice of “self-help” rather than talking about my own emotions.

When I spend almost all day in solitude, when there’s no more workflow to optimize, confrontation with myself becomes inevitable. The uplifting language that worked perfectly well in the previous reality no longer feels sufficient. Modern tools and platforms have largely facilitated connecting us as nodes and sorting us into clusters, but we’ve approached its limit to unravel the complexity of our own emotions.

Without a deep understanding of ourselves, we also become inept at understanding others, especially those who share the same world but a different reality. And without a deep understanding of others, it’s almost impossible to build, even when tools are getting friendlier, and more accessible than ever.

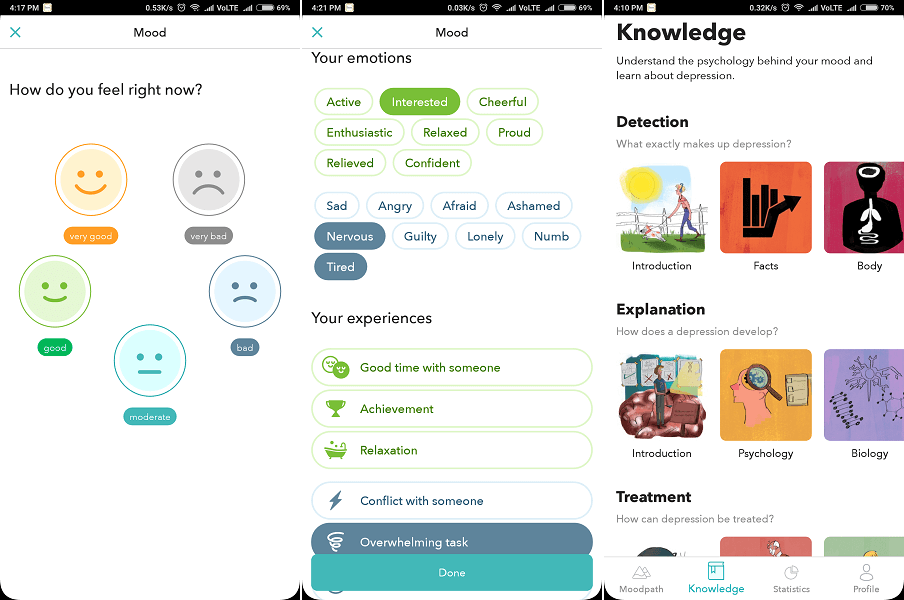

The app Moodpath helps name your emotions. A few clicks of a button demarcate the territory of possibility, anything outside of the screen feels like an irrational anomaly.

The app Moodpath helps name your emotions. A few clicks of a button demarcate the territory of possibility, anything outside of the screen feels like an irrational anomaly. Facebook adds “Care” to the COVID-19 emotional collection. I’m curious to see the data around how much less I write to my friends ever since the rollout of the “reaction” feature across Facebook, Apple, and Slack.

Facebook adds “Care” to the COVID-19 emotional collection. I’m curious to see the data around how much less I write to my friends ever since the rollout of the “reaction” feature across Facebook, Apple, and Slack.For most of history, humans’ emotional education was broadly created by religions, and with the greatest authority, they taught us about ethics, they provided meaning, community, and purpose. And for a long time, consumer culture has attempted to fill the chasm, but it’s increasingly obvious that stories have been written for only a handful of us.

When “human needs” get operationalized as purchasing power, under conditions of inequality, resources get allocated to not to where they are most needed, but those who have access to the most capital. While the pursuit of profit has been an effective motivator creating productivity and for rewarding those who are productive with buying power, it is now producing a self-reinforcing feedback loop that widens the income, wealth, and opportunity gap to the point where the story of American Dream is in jeopardy.

Consumer culture has anesthetized the need for deep emotional connection and spiritual maturity. Tara Isabella Burton has one of the best portrayals of this peculiar power dynamics of capitalistic worship:

In SoulCycle, in other words, bodily mortification leads to transformation, just as it does in most Western religions: think of the hair shirts of medieval Catholics or Methodist circuit riders who gained fame for their harsh practices of fasting and praying on their knees in painful positions for hours at a time. But at SoulCycle, the spiritual goal is not to enter into communion with a higher power but is an end in itself.

[…]

Purveyors of wellness have long said that the body is a temple. But at SoulCycle, at least, the body is worshipper, temple and deity alike.

The last global crisis in 2008 exposed fraudulent Wall Street practices, which led to a need for more transparency. “Transparency” soon became a key value for brands to showcase. The birth of brands like Warby Parker, Casper, Uber, and Lululemon all reflected the need for transparency and benevolent business practices through community building, completely changing the way established markets had operated.

The current crisis will give birth to a new narrative revolution. Unmanned infrastructure, digitally-only services, contactless interactions, fragmented identities, coupled with massive yet impalpable changes only intensify our desire to be seen, be heard, and to be understood. If we look at religious history, one solution to the fragilities of human minds is art — architecture, music, painting, etc.

For a while in our capitalistic history, we dismiss art as elusive, impractical, and even self-indulgent. We forget that for most of history art has a direct purpose as a tool of education. The point of art is to create the kind of beauty that makes us feel less alone, to render tough lessons easier to absorb, to amplify perspectives we tend to overlook, to nudge us towards seeing reality as a canvas of possibility.

This crisis is forcing us to contend with an even wider question implicit throughout the digital age. What is art in the age of the internet? Zoom, Netflix, and even Fortnite seem insufficient. They are canvases, not art.

How can art respond to both the possibility of this intense need for human intimacy and yet celebrate the internet’s capacity for freedom? How can the internet allow us to express, and experience, emotional vulnerability — the cornerstone of human connections? For now, these questions of what it means to be digitally present, and what a constructive, inclusive, and aesthetic digital space might look like remain largely unexplored.

I once wrote about how founders are artists. Like artists, the best founders I know possess the sensitivity to people’s pleasures and pains that others might overlook, or not take seriously enough to spend time thinking about. What distinguishes an artist is that they use their sensitivity to create an alternative version of reality through music, films, or imagery. For founders, instead of just showing others how nice this could be, the business directly enables other people to have the same satisfaction themselves. And it is then able to share this pleasure on a very large scale.

And to create good art, we want to meet where people are. The world-building activities that we are seeing on the internet give me hope that we are treading towards the consilience of these visions.