IDEAS THAT AFFECTED US LIKE A DISASTER

July 2020

Sometimes we forget why we read. If we agree with everything we read, then what use is education?

Recently, the two extremes of the debate are converging into one ideology, one that neglects the in-between and eventually threatens not only democracy. As Orwell wrote in 1946 essay “The Prevention of Literature”:

What is sinister is that the conscious enemies of liberty are those to whom liberty ought to mean most […] They do not see that any attack on intellectual liberty, and on the concept of objective truth, threatens, in the long run, every department of thought.

That includes technology, includes the arts, includes things we hold dear as humans. Increasingly so, what is important is not so much to defend culture as to extract ideas whose force is identical with that of hunger.

Franz Kafka, at the age 20, wrote in a letter to his friend Pollack:

I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound and stab us. If the book we’re reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow on the head, what are we reading it for? So that it will make us happy, as you write? Good Lord, we would be happy precisely if we had no books, and the kind of books that make us happy are the kind we could write ourselves if we had to. But we need the books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us. That is my belief.

French philosopher George Bataille, in the preface to his novel Le Bleu du ciel, makes a similar distinction between books that are written for the sake of experiments and books that are born of necessity. He argues, literature is an essential disruptive force, a presence confronted in “fear and trembling” that is capable of revealing the truth of life and its excessive possibilities. Literature is not a continuum, but a series of dislocations. Books that mean most to us are usually those that ran counter to the literature that prevailed at the time they were written. He importantly pointed out “the moment of rage” — the kindling spark of all great works, violently, and urgently, changing our perception of the world.

Sometimes we forget why we read. If we agree with everything we read, what use is education? If the default expectation is amenability, then there are no more paths to be chosen. The diversity we claim to value doesn’t come from amenability, but discomfort, distaste, and even disgust, through which we then find the outline of our beliefs. We can hold on to them or not. That is a choice.

Sometimes we forget that civilization is constructed with a series of these choices.

On the Shore (Sur la rive) 此岸, 2016 | Gao Xingjian.

On the Shore (Sur la rive) 此岸, 2016 | Gao Xingjian.Gao Xingjian, Chinese émigré (or exile) artist, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2000. As a young adult, Gao Xingjian was already a writer with an obsessive desire for self-expression. However, he was aware that what he wrote was clearly at odds with Mao’s directive that literature and the arts must “serve the masses.”

During the Chinese Cultural Revolution, when stringent measures were imposed on intellectuals and artists, he knew that his writings were highly problematic and would never see the light of day. Yet as a compulsive writer, he continued to write. Even while undergoing “re-education” and living the life of a peasant in the 1970s, he continued to write but took the precaution of wrapping his manuscripts in plastic and burying them in the earth floor under the heavy water vat in his hut.

At the height of the Cultural Revolution, rather than risk having to face dire consequences for his accumulated writings, he burned several kilos of manuscripts (ten plays, and many short stories, poems, and essays). It took a long time to burn so much paper without creating smoke and arousing suspicions.

In 1987, he was able to travel to France as a painter and began what he described as his "second life". He sought political asylum in France and was granted French citizenship two years later: “After I went to France, I finally had an environment where I could work freely," he said. "So you could say I worked extremely hard, but I was very happy."

In an interview, he was asked what it means to be a writer either in exile or as part of a diaspora:

At one level, I think that in the twentieth century the problem of exile or alienation is particularly pronounced for writers and artists.

At another level, a more spiritual level, that exile also means overcoming ideologies and overcoming prevalent attitudes and trends, and so exile has also been a way of pursuing “no -isms” or overcoming ideologies.

At a third level artists tend to be on the margins of society. So from that perspective, exile is a kind of appropriate mental state, at least for artists. This is a good thing. If you are in the center of society, you will be receiving inputs and pressures from too many different areas, and that is not the kind of environment that an artist needs to cultivate his own creativity and his own thinking.

Gao represents the underrated yet increasingly frequent persons who are “in-between”— that is, in-between the still reigning paradigm of national and cultural identities.

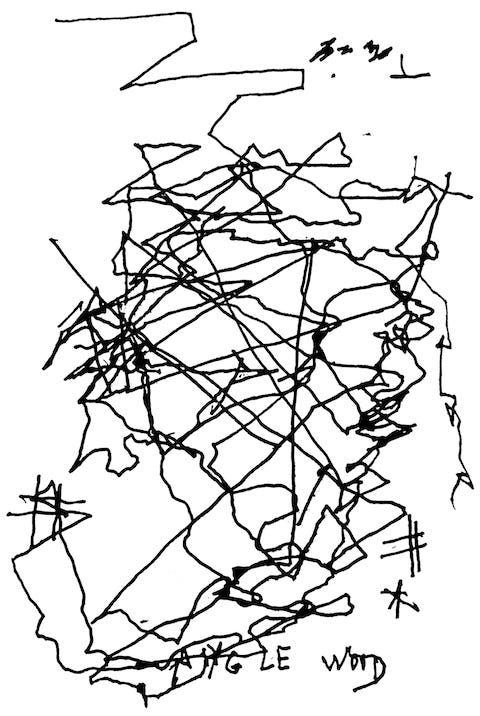

It was after his final descent into near-blindness that Jorge Luis Borges drew this self-portrait for in the basement of Strand Bookstore in New York City.

One of the great writers to come out of Argentina, Borges shared with The New York Times, "I knew I would go blind, because my father, my paternal grandmother, my great-grandfather, they had all gone blind.”

He wasn’t exactly sorry to be blind. “A writer, or any man, must believe that whatever happens to him is an instrument, everything has been given for an end,” he wrote:

Everything that happens, including humiliations, embarrassments, misfortunes, all has been given like clay, like material for one’s art. One must accept it. . . If a blind man thinks this way, he is saved. Blindness is a gift. I have exhausted you with the gifts it has given me.

The self-portrait above, which he created by "using one finger to guide the pen he was holding with his other hand,” feels like a delineation of what has given shape to his soul. Crooks and turns. Full of the unexpected. After making the sketch, Borges entered the main part Strand and started "listening to the room, the stacks, the books," and afterward made a remarkable observation: "you have as many books as we have in our national library.”

The grace of transforming one’s personal crisis is no less noble than the heroic attempt of saving a nation. What is more interesting is how an individual, who is not a hero, find their path through disasters and crises.

And if everyone is a hero, then disasters and atrocities lose their meaning. It is only when certain people are heroes, and others are not that the tragedies and disasters take on meaning.